In September I started teaching at Michaela.

What drew me there? The first thing was Michaela’s mathagogy. Over the summer, I reflected on my experiences as a maths teacher in the series ‘Is this the best we can do? Doing better’, looking at issues with UK maths education such as work ethic, textbooks, pedagogy, subject knowledge, expectations, behaviour. Much of the inspiration from this series has come from Michaela teachers. (I didn’t quite write all the posts I was intending to write – but I’m hoping to finish off the series, especially in light of my experiences at Michaela, trying to put some of these into practise.) I’ve been eagerly following Michaela blogs since the school started, and found myself nodding along to(/exuberantly absorbing) many of their thoughts – for example, on recall, or the foundations of teaching problem solving; or teaching efficiency in strategies; or on making textbooks. So it felt like a natural fit.

And then I visited. Watching one of the maths team teach an hour of maths was one of the highlights of my year, and that one hour hugely transformed my own teaching practice when I returned to my previous school. (To list a few things, I started speaking much faster in lesson, expected 100% attention, encouraged pupils to take more responsibility for their results, heightened my own expectations, and showed my own personality more. All from watching her for an hour!) I knew I wanted to work there. More than that, I knew that I couldn’t bring about my thoughts on maths education all by myself – such as making textbooks, or setting daily homework, or regular testing – but Michaela seemed to be doing it all, and more, already.

Those things drew me to work there. I’ve been there for a month. How has it been? Here are some reflections.

Firstly, it’s been a great joy to work with the maths department. We spent a whole hour yesterday discussing how to teach vertically opposite angles. In the end we were debating whether it needed 2 hours of lesson time or 3 (!). In the past, I’ve spent perhaps 10 minutes on it over a whole year. But then again, I never dreamed of teaching problems like this:

(I asked whether the new GCSE really would be this hard (since I have an inkling most schools aren’t quite teaching in such depth!); my boss then whipped out a circle theorems + angles in polygons problem from the new Sample Assessment Materials, which we then took 5 minutes to do together. Conclusions: (a) The new GCSE will be this hard. (b) We have the best meetings!)

I could wax lyrical about the things we think about in the department, and I may do at some point, but we’ve already got great blogs here and here in explaining some of the mathagogy we spend our time thinking about. I can’t resist putting in the most important insight though. The biggest and most revelatory mindset shift in Michaela’s mathagogy is this: never think ‘what do I want pupils to learn today?’; instead, think ‘what do I want pupils to remember for the next year/five years?’ – and plan each lesson accordingly, with lots of recap, interleaving, drilling, and quizzing to push back the forgetting curve. As a result, with one of my more-forgetful classes, I can spend over 50% of each lesson purely on recap and revision of past content.

But I was expecting all the above – that’s what I signed up for. Here were some of the surprises, or rather revelations.

The vital importance of behaviour. In my career I’ve put most of my interest in maths pedagogy, as my blogging shows. This was due to a concern that I wasn’t teaching nearly well enough, that my pupils weren’t benefiting from the most cutting edge pedagogy, which meant they weren’t doing as well as they could. But in coming to Michaela I’ve seen that improving behaviour for learning is of even greater importance. I don’t even mean getting pupils to listen, pay attention, not be distracted (and the pupils are great at that at Michaela!). There is a relentless focus on efficient routines at Michaela. It takes around 60 seconds for my class to get through the door, be seated, and be fully engaged in a ‘Do Now’. At the end of a lesson it takes them 30 seconds to pass exercise books & textbooks back to the windowsill and be standing silently behind their chairs. It is breathtaking to see. Even more crucial is the why. It was 10:10; I had just finished a whiteboard activity on a newly-learnt procedure; my class had to be fully out of my classroom by 10:14. But because of those routines, I managed to squeeze in: a 20 question textbook drill (which some of the pupils completed), whole-class marking of the answers (most of the class got 100%), pack-up time, and then a quick run-down of who’d done most questions on IXL that night. I love it; the pupils love it. I’ve blogged before on the importance of time. In Stephen Tierney’s words, ‘you can only spend it once‘ – and it’s a great joy to be a school where every second counts.

Relatedly, behaviour systems and high expectations have been a huge joy. I always thought that at best, I was ‘good enough’ at behaviour. Previously, I had to manage my classroom behaviour entirely by myself, 98% of my pupils would focus whilst I was explaining, and, for the most part, work reasonably hard in lessons, but some of the pupils never fully learnt not to shout out; nor were my lessons totally free of immaturity. Coming to Michaela, where expectations upon the pupils are crystal clear, has helped me change enormously. We expect 100% effort and focus, 100% of the time. Warnings and demerits are given for being distracted, bad reactions, anything that isn’t 100%. And a centrally managed behaviour system has liberated me to raise my expectations – I’m able to give detentions because I know I don’t have to chase that child around the school at lunchtime. As a result, the behaviour is extraordinary. I wonder how much of my past difficulties in getting pupils to learn maths was due to not expecting 100% focus, 100% of the time. Good pedagogy is vital but totally wasted if pupils feel able to drift off. How much of my past teaching was let down by this?

One of my favourite things I’ve learnt has been narrating my behaviour management. Every single action of behaviour management is accompanied by an explanation; sometimes as short as ‘you’re fiddling; we focus, so we can learn’; sometimes a more extensive explanation of how not doing your homework now means you fall behind in your learning which means you won’t get another topic in year 8 which means you’ll have real trouble with maths which means you might not pass it which means you’ll find it hard to get a good job which means you’ll find life difficult later on. We always, always, emphasise how our sanctions come from our care for them and for their happiness. As a result of narration, pupils’ buy-in at the school is extraordinary. At lunchtime, pupil after pupil explains to you how they used to be naughty, but now they are glad they’ve learnt to ‘work hard and be kind‘ (the school motto) so they can become a better person and have a good future. It can get quite emotional. In the first week, one year 7 told me how she was so inspired by one lesson she went home and asked her mum to teach her how to do the laundry, so she could do it for her mum. Sometimes you even get cards like this:

We all know Michaela for its controversial focus on an academic curriculum, but no one ever prepared me for how the most extraordinary character education is happening here too.

It’s also worth saying that the excellent behaviour has let me ‘let down my hair’ in my lessons; I’m more energetic, ridiculous, light-hearted in my teaching, than ever before – because I know that I can do things like call silly mistakes ‘brain farts’ without worrying about immature pupils taking liberties.

Because the pedagogy at Michaela is so well thought-through, pupils unashamedly love learning. A particular difference brought this home to me. I love Marland’s book ‘The Craft of the Classroom’ and one of his bits of advice was ‘never start a question with ‘Does anyone know…?’ One of my Teach First tutors agreed: when questioning, skip all identifiers like ‘who knows?’ and keep the question free of anything that requires pupils to identify themselves with an answer: they might be embarrassed, or unsure, or anxious, or not wanting to seem too keen – just go straight to the question so the focus is on the topic itself. I think it’s generally good advice. But interestingly, I saw an English teacher using this phrase every question; and then I saw a maths teacher using it – and in both cases, there was an abundance of hands shooting up around the classroom. I started to trial it. Old habits are hard to break, so it started coming out like this: ‘Where should I put the commas? Where do I put them? … Who can tell me?’ – and fascinatingly, at the ‘who can tell me’, more hands would pop up, and the hands already up would shoot even higher. My interpretation: pupils across the school unashamedly love learning and are proud to be so knowledgeable. What a gift to teach at such a school! Other demonstrations of this: I’ve had classes pleading with me to show them the Gelosia lattice, and when I finally did so, the joy was palpably leaking out of their agape mouths; I’ve had classes pleading to be given ‘a harder question’ so they could truly test the limits of their knowledge; I’ve even spent an hour over two lessons fielding questions about income tax and the personal allowance during a percentages lesson. They just love learning. What a gift!

More generally it’s a great place to develop as a teacher. I haven’t had to fill out a single piece of paperwork – including lesson plans – yet I’ve been observed at least 10 times over this month. But the observations are entirely formative – we don’t have PRP or grades or performance management. Everyone simply wants all the help they can get to become a better teacher. The feedback is fantastic: on point and straight to the point – ‘don’t say this, it’s encouraging a fixed mindset’; ‘try ‘; ‘watch this pupil like a hawk, he’s turning around every time you’re at the board!’. All of this combines to make the sort of culture you dream of working in, but never think is actually possible. I’m popping into a colleague’s room, asking her to observe me with a particular class because I’d love her perspective on why we’re moving a bit slowly through the content. When I first visited Michaela, I thought one big reason it was an excellent school was because it had simply recruited the very best teachers. But now I see that the culture of feedback and strong school-wide systems have made each teacher become as good as they can be.

Some quicker reflections:

- I’ve not had to work a single weekend, and I’ve worked during an evening at home only once – for 15 minutes.

- More on the no-paperwork front: everything I’ve been asked to do has had a directly tangible effect on pupil outcomes; I haven’t been asked for a single piece of ‘evidence’.

- I haven’t used a powerpoint lesson all year – the quality of the (in-house made) textbooks is incredible. For the first time I’ve noticed there’s a difference between planning and resourcing. I now spend my time reading the textbook, deciding on structuring, thinking about the key phrases to chant, what bits to emphasise in the worked examples.

- Since every minute at Michaela is so purposeful – someone described our teaching as ‘taut’ – the time flies. I clock-watch, but in the opposite sense: I look up to find that 40 minutes have gone and I’m really sad that I’ve only got 20 minutes left to teach the wonderful children in front of me.

- I’ve learnt to eat faster than I ever thought possible.

- Thanks to breaktime snacks provided for pupils and staff, I’ve been eating a piece of fruit every single day for the first time in my life. I’ve even bought some for home.

- I’ve learnt to click my fingers for the first time ever. It’s a surprisingly powerful strategy for regaining a drifting pupil’s attention that we use all the time.

- I’m a form co-tutor and I absolutely love form time. We have 50 minutes of it over the day, and I’ve spent most of it this year reading David Copperfield and Catcher in the Rye aloud with my form. It’s a brilliant way to start and end each day – I had to suppress a tear or two at the end of David Copperfield – and the pupils love it too! (I think they’ve taken to Catcher in the Rye a bit more quickly than David Copperfield – but they were strangely scandalised by the ending of the latter, too…)

Last but not least, it’s a place filled with love. Yesterday after school, at the end of the working week, several members of the maths department and I were doing a mix of textbook writing and chatting. To be honest, we had spent most of our time chatting. The focus of our chat? Some of our favourite and most hilarious moments with our pupils that week.

It was a heart-warming way to leave for the weekend. It’s a heart-warming place to work.

Interested in joining the maths team? We’re recruiting! The team are inspirational! We’re looking for a teacher for September 2017 (or sooner, for the right candidate). The ad is on TES now, closing SOON: https://www.tes.com/jobs/vacancy/maths-teacher-brent-440947

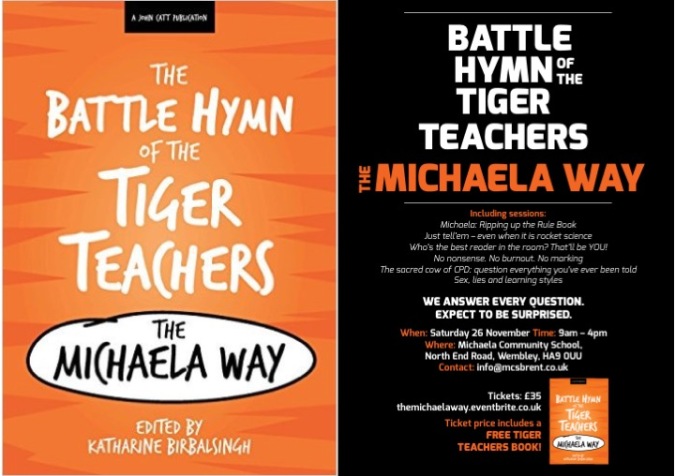

Interested in finding out more about Michaela? Book a ticket to our book launch – details below! We’re almost sold-out. Or pre-order the book here.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

LikeLike

Pingback: Bootcamp | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: The Blogosphere in 2016: Roaring Tigers, Hidden Dragons | Pragmatic Education

Hello Hin-Tai,

I’ve been reading your chapter in BHOTT on the lack of respect for teachers. I’m interested in the practical implications of your beliefs: if a class is being disruptive, would you advise the teacher to remind the class of the need to be respectful? Do you think repeatedly demanding respect is a good way to improve discipline in the classroom? I enjoyed your chapter, it’s full of interesting insights and observations, but I’m just not sure how your ideas apply to ‘normal’ schools where discipline isn’t as good as in Michaela.

Thanks,

An Timire

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment. Practical implications is a harder question! I’m very thankful for the school-wide expectations and systems at Michaela where every teacher is consistently promoting, expecting, appreciating respect, and modelling kindness and politeness to pupils. So it’s hard to transfer to another context.

Here are some preliminary thoughts: there are better and worse ways of ‘demanding respect’. One thing that worked well in my previous school was firstly calling out obvious rudeness – for example, where pupils were tutting at me or kissing their teeth. Secondly, point out explicitly and make a big deal of how (truthfully) hard you work for your kids, how much you care about them, how polite and kind you are, how you spent your saturday creating this lesson for them, etc.. In other words, as teachers, we do so much for our classes that they take for granted – stop them taking it for granted by making it explicit, so that they know exactly why you demand their respect. Some lines from teachers here: ‘I don’t deserve this treatment from you. I work incredibly hard for you. I was in school at 7:15am marking your tests so you can know how well you did. On Sunday, instead of spending time with my wife, I spent my afternoon creating this lesson, and you come into my lesson and [do that behaviour]. That is totally unfair.’ I guess what I’m saying is – a good starting place is to really flesh out the many true reasons why pupils should respect us, so that they start to see that ‘yes, it is wrong for me to be so disrespectful’. Narration is key. Without narration, it can sound entitled or tyrannical, which doesn’t get any buy in.

As for whether it’s a good way to improve discipline, I think it’s the cherry on the cake, but not the central key – I think it takes a mixture of continual narration and reason-giving, centralised detention systems, high expectations across a school, and constant alertness. Jonny Porter’s chapter is a good read for that. Demanding respect without all those together components might not be feasible. Hope that helps.

LikeLike

Pingback: Teaching mathematical grammar | mathagogy

Pingback: Is this the best we can do? Part 6: the problem of forgetting | mathagogy

Pingback: Bootcamp | Best bets